The Uncomfortable Truth: Why India Can’t Afford to Kill Its $250 Billion “Delivery Boy” Economy

Weekly Newsletter - Paper by Pocketful

India’s startup ecosystem has entered an unusually political phase. What began as a story of entrepreneurship, job creation, and digital adoption is now increasingly framed as a moral and regulatory debate about dignity, safety, and the “quality” of innovation.

Recently, Raghav Chadha publicly welcomed government action against the “10-minute delivery” promise in quick commerce, presenting it as a necessary intervention to protect gig workers from unsafe conditions. This framing echoes a broader skepticism voiced earlier by Piyush Goyal, who famously criticised Indian startups for producing “delivery boys” instead of building globally competitive deep-tech companies like those in China or the United States.

For public discourse, these statements play well. They sound pro-worker, pro-innovation, and morally grounded. For investors, however, they raise far more uncomfortable questions. Because behind the rhetoric sits a hard economic reality- India’s gig and platform-led delivery economy is no longer a fringe experiment. It is a labour absorption engine of national significance, intertwined with consumption, urban mobility, logistics, and household incomes at scale.

Importantly, this scepticism toward platform models is not limited to delivery. It is already visible in mobility, where bike-taxi platforms have faced bans and regulatory pushback in several states. These conflicts hint at a broader policy tension between protecting legacy systems and allowing newer, more efficient models to scale. The full implications of this trend become clearer when we examine why India is one of the few markets where such platforms actually work.

The real question is not whether gig work has flaws. We know it does. The real question is whether India can afford to choke a sector that will soon make up more than 1% of its entire GDP. If the government shuts down or heavily regulates these platforms, what happens next?

There is no clear plan to replace the millions of jobs or the massive household incomes these companies provide. This is not just about political ideas. It is a major economic challenge. Without these startups, India faces a huge gap in employment that the government cannot easily fill. Investors need to look past the speeches and see that for millions of Indians, this “delivery economy” is a vital lifeline that the country simply cannot afford to lose.This is not an ideological debate. It is a macroeconomic one.

The Macro Thesis: A $250 Billion Reality Check

Before discussing bans, restrictions, or moral judgments, investors must first internalise the sheer scale of what is being debated.

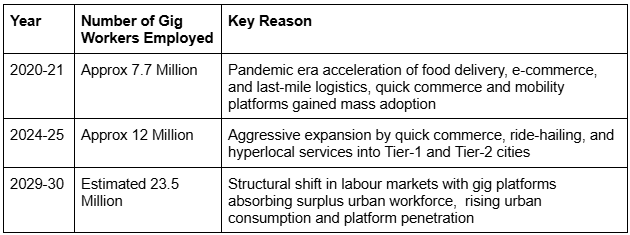

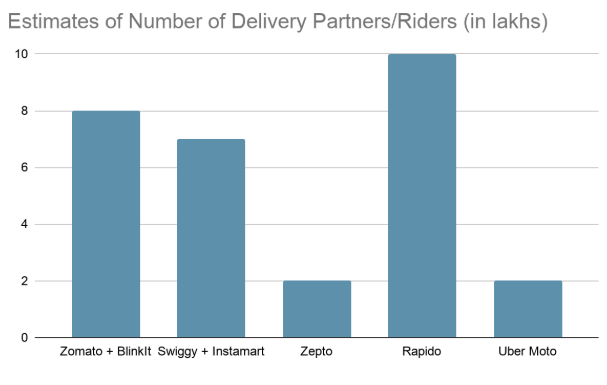

India’s gig economy is not a buzzword. It is a structural labour market phenomenon. According to NITI Aayog estimates, India already had approximately 12 million gig workers in 2025. These include food delivery riders, grocery pickers, bike-taxi drivers, last-mile logistics partners, and platform-based service workers. This figure alone places the gig economy on par with some of India’s largest organised employment sectors.

More importantly, the direction of travel is unmistakable. Projections suggest this workforce could expand to 23.5 million workers by 2029–30. That is not incremental growth—it is a threefold expansion in less than a decade.

From an economic standpoint, this growth is not accidental. India’s demographic structure, urbanisation pace, and informal to semi-formal labour transition create fertile ground for platform-mediated work. Millions of young workers are entering cities without the formal credentials required for white-collar jobs, while traditional manufacturing absorption remains slow and capital-intensive.

Estimates suggest that, at maturity, the gig economy could generate around $250 billion in economic value and contribute more than 1% to India’s GDP. For context, that places it in the same macro category as several legacy industries that receive explicit policy protection and subsidies.

Against this backdrop, calls to “shut down” or aggressively constrain gig platforms are not minor regulatory tweaks. They represent a willingness to disrupt a labour market mechanism that is currently doing something India has historically struggled to achieve: absorbing millions of workers quickly, at relatively high income levels, without massive public spending.

The Global Graveyard: Why the West Failed

Critics often argue that India’s quick commerce and gig delivery boom is merely a shallow imitation of failed Western models. The evidence from the US and Europe, however, does not support that simplification.

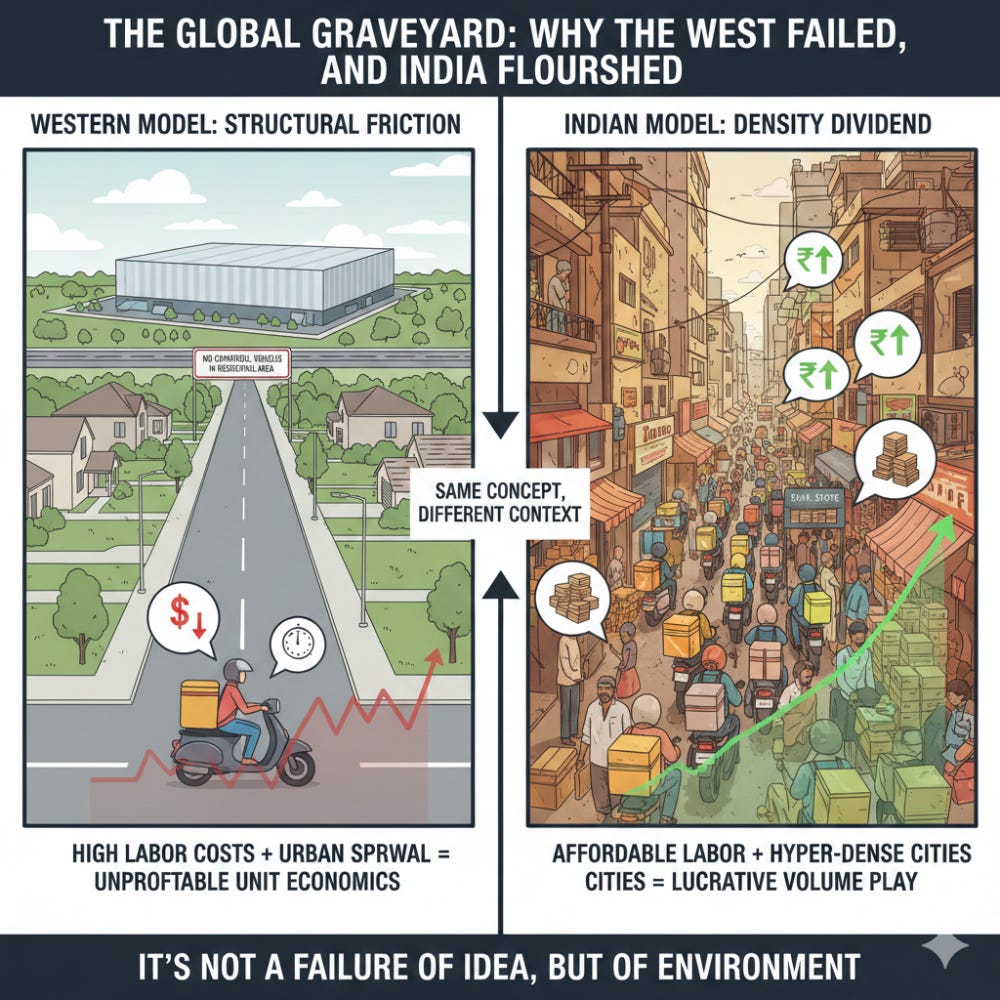

Quick commerce did indeed collapse across much of the West. Companies that promised ultra-fast grocery delivery burned through billions before retreating or shutting down entirely. But the reason was not conceptual failure—it was economic incompatibility.

In the US and Europe, labour costs are structurally high. Riders and warehouse workers are paid fixed hourly wages, often exceeding $15 per hour, with mandatory benefits, insurance, and regulatory compliance layered on top. At the same time, suburban sprawl dramatically reduces order density. Riders cover larger distances for fewer orders, while zoning laws push warehouses away from residential areas.

The result is a lethal mismatch. A rider waiting for an order that generates only a few euros of gross margin quickly turns the entire operation cash-negative. No amount of operational optimization can overcome that arithmetic.

India’s policymakers often cite these Western failures as cautionary tales. What they miss is that these failures say very little about India’s viability. They instead highlight why the same model behaves radically differently under different labour and urban conditions.

The Getir Lesson: Why This Model Only Survives in the Right Conditions

The failures of quick commerce in the US and Europe were not random. They followed a clear pattern, best illustrated by the rise and retreat of Getir, one of the earliest and most well-funded players in the sector.

Getir built and perfected the ultra fast last-mile delivery model in Istanbul. There, the business worked exactly as designed. The city’s dense, vertical housing meant a single rider could serve multiple customers within minutes, often from the same building. High order frequency and short travel distances kept delivery costs low and rider productivity high.

The problems began when Getir expanded into Western markets such as the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, and the US. These regions are dominated by spread-out neighbourhoods and suburban layouts. Riders had to travel much longer distances for each order, sharply reducing the number of deliveries per hour. Once order density dropped, the economics collapsed.

Labour costs made the situation worse. In Europe and the US, riders are paid high fixed hourly wages, often $15 to $20 per hour, along with benefits and regulatory costs. That wage structure simply does not work for a business where each order generates only a small margin. Customers were not willing to pay significantly higher prices just to receive groceries faster.

By 2024, Getir was forced to exit most Western markets and retreat to Turkey, the only geography where dense cities and affordable labour made the model viable.

This experience shows a simple truth. Quick commerce is not a universal model. It only works in places with very high population density and relatively low labour costs. India is one of the few large economies that meets both conditions at scale, which explains why the model failed in the West but continues to grow here.

The Indian Exception: An Operational, Not Ideological, Advantage

India’s success with quick commerce is not the result of regulatory leniency or reckless capitalism. It works because India’s basic economic structure fits the model unusually well.

First is urban density. Indian cities pack thousands of households into very small areas. A delivery radius of just 2–3 kilometres can include tens of thousands of potential customers. This allows riders to complete more orders per hour, keeps delivery times short, and makes last-mile logistics economically viable.

Second is labour economics. While worker protections must improve, the reality is that labour costs in India are far lower than in developed markets. This allows platforms to keep riders and warehouse pickers productively engaged instead of paying high hourly wages for idle time, a problem that destroyed quick commerce in the US and Europe.

Third is consumer behaviour. Indian households are already used to frequent, small purchases. Limited storage space, small kitchens, and daily buying habits existed long before apps. Quick commerce did not create this demand; it simply digitised the neighbourhood kirana model and scaled it using data, inventory management, and routing technology. This is localisation, not copy-paste innovation.

The regulatory tension around delivery platforms is not an isolated phenomenon. It mirrors a broader hostility toward platform-enabled mobility, most visibly in the treatment of bike taxis.

In the past, states like Karnataka and Delhi, bike-taxi services operated by platforms such as Uber Moto and Rapido have faced bans following court rulings that restrict the commercial use of private motorcycles.

On paper, the justification is legal compliance. In practice, the political economy tells a more complex story. Auto-rickshaw unions are powerful, organised, and vocal. Bike taxis directly undercut their pricing power by offering faster, cheaper alternatives. A ₹30 bike-taxi ride replacing a ₹100 auto ride is not merely a convenience shift, it is a redistribution of consumer surplus.

When bike taxis are banned, consumers pay more, mobility becomes less accessible, and thousands of riders lose income overnight. The beneficiary is not worker welfare in aggregate, but a protected legacy segment.

This pattern is worrying for everyone. It signals a regulatory instinct to preserve incumbents even when newer models deliver superior efficiency and consumer outcomes. If extended broadly, such protectionism risks freezing productivity gains precisely when India needs them most.

Why Workers Join: Debunking the “Forced Labour” Narrative

A common critique of gig work is that workers are “forced” into these roles due to lack of alternatives. Reality is more nuanced.

Survey data consistently shows that flexibility is the single biggest driver of participation. Nearly half of gig workers cite the ability to balance work with family or education as a primary motivation. Fixed shifts in factories, retail, or security jobs rarely offer this autonomy.

For over half of participants, gig work functions as supplemental income. Students, migrants, and informal workers use platforms to smooth cash flow rather than replace full-time employment. For them, banning platforms removes optionality, not exploitation.

Crucially, for around 22% of workers, gig work is the only viable income source. These individuals often lack formal education, networks, or geographic stability. Platform work allows them to monetise time and effort without gatekeepers.

This does not negate the existence of genuine grievances around safety, algorithmic opacity, or income volatility. But it does dismantle the simplistic narrative that workers are uniformly coerced. Many are making rational trade-offs in a constrained labour market.

The Income Reality: ₹25,000–₹35,000 and the Top-10% Effect

The most uncomfortable fact in this entire debate is also the most ignored.

In major Indian cities, diligent delivery riders and bike-taxi partners routinely earn ₹25,000 to ₹35,000 per month. This figure fluctuates with hours worked, location, and incentives, but it remains directionally consistent across platforms.

In absolute terms, this may not sound extraordinary. In relative terms, it is transformative. National income data shows that earning ₹25,000 per month places an individual within the top 10% of income earners in India. That means gig platforms have effectively opened a pathway for uncredentialed workers to enter the upper decile of the income distribution through sheer effort.

This is not a trivial achievement in a country where millions of graduates struggle to find jobs paying half that amount. Labeling such outcomes as “exploitation” without presenting viable alternatives is intellectually dishonest. The real question is not whether gig work is hard—it is whether the alternatives are better. For most workers, they are not.

Income distribution drives consumption, credit access, and social stability. Platforms that lift large populations into higher earning brackets generate second-order economic benefits far beyond delivery fees.

Beyond Delivery: The Gig Model’s Second Act

The popular “delivery boy” label badly understates where the gig economy in India is headed. Food and grocery delivery may be the most visible face of platform work today, but it is not the final destination of the model. It is merely the entry point.

Transport and logistics currently dominate gig employment because they were the easiest sectors to digitise first. Demand was obvious, transactions were frequent, and technology could quickly match workers with tasks. But the same platform logic is now spreading into far larger and more economically important sectors such as construction, assembly, warehousing, and organised retail operations.

These industries share deep structural problems. Contracting is fragmented, labour matching is inefficient, attendance is unpredictable, and productivity varies widely. Workers often rely on informal contractors, while employers struggle with delays, quality issues, and lack of accountability. Platform mediation can significantly reduce these frictions. By standardising work allocation, tracking performance, and enabling transparent payments, gig platforms can bring predictability and scale to sectors that have remained informal for decades.

For India, this matters far more than food delivery. Construction and manufacturing support jobs sit at the heart of India’s ambition to compete with China as a global production hub. Without reliable, flexible labour systems, those ambitions remain theoretical.

This is why regulatory pressure focused narrowly on delivery and mobility carries hidden risks. If policymakers weaken or delegitimise the gig model at its most visible edge, they risk discouraging its adoption in these higher-impact sectors. The cost is not just fewer delivery jobs. It is the loss of future productivity gains across the broader economy.

Conclusion: Regulation, Not Strangulation

This debate ultimately comes down to a trade-off India cannot afford to make. If the country bans or suffocates the so-called “delivery boy” economy, it does not magically produce deep-tech scientists, semiconductor engineers, or AI researchers. It produces unemployed youth. That outcome helps neither innovation nor social stability.

None of this is an argument against regulation. Gig work must become safer, more transparent, and more secure. Workers deserve accident insurance, grievance redressal, predictable payments, and basic social security. On this, there should be no disagreement. Crucially, the policy tools to achieve this already exist. The Social Security Code 2020 formally recognises gig workers as a distinct category, while the Code on Wages 2019 sets a national floor for earnings. What is missing is implementation, not intent.

From an investor’s perspective, the choice before India is clear. The country can formalise and strengthen a labour market innovation that is already absorbing millions of workers at scale, or it can dismantle it in the hope that something better will emerge on its own. History suggests that hope is not an economic strategy.

Calls for deep-tech innovation are valid. India must build advanced manufacturing, semiconductors, and high-end technology capabilities. But this does not require destroying the gig economy. China did not abandon low-skill employment to pursue advanced industry; it built both in parallel. India can do the same. Gig platforms and deep tech are not rivals. They serve different layers of the economy and solve different problems.

For policymakers, the responsibility is heavier than rhetoric. Before dismantling gig platforms in pursuit of an idealised vision of innovation, they must answer a simple question: what alternative do you offer to the 23.5 million people expected to depend on gig work by the end of this decade?

Until that answer exists, India cannot afford to kill this sector. It can only afford to formalise it.

LINGO OF THE WEEK

GDP-by-Absorption

GDP-by-Absorption refers to economic growth created not through high productivity or technological breakthroughs, but by absorbing large numbers of workers into income-generating activity. Millions earning modest but steady incomes collectively expand consumption, credit flow, and demand. The growth looks unimpressive per worker, yet becomes macro-significant at scale, stabilising the economy without heavy public expenditure.

Pocketful isn’t just another trading platform - we’re your partners on the journey to financial freedom.

Thank you for reading!

👀 Stay tuned. Stay diversified.

Until next time,

Team Pocketful.

Follow Us: Website

Download Our App: Available on Google Play & Apple App Store