Some days in the market feel oddly familiar. A headline flashes “Government hikes tobacco taxes, ITC falls sharply” yet reactions vary. One investor feels vindicated, another panics, a third shrugs and says this has happened before. Prices move within minutes, narratives form within hours, but the real impact beneath them plays out over years.

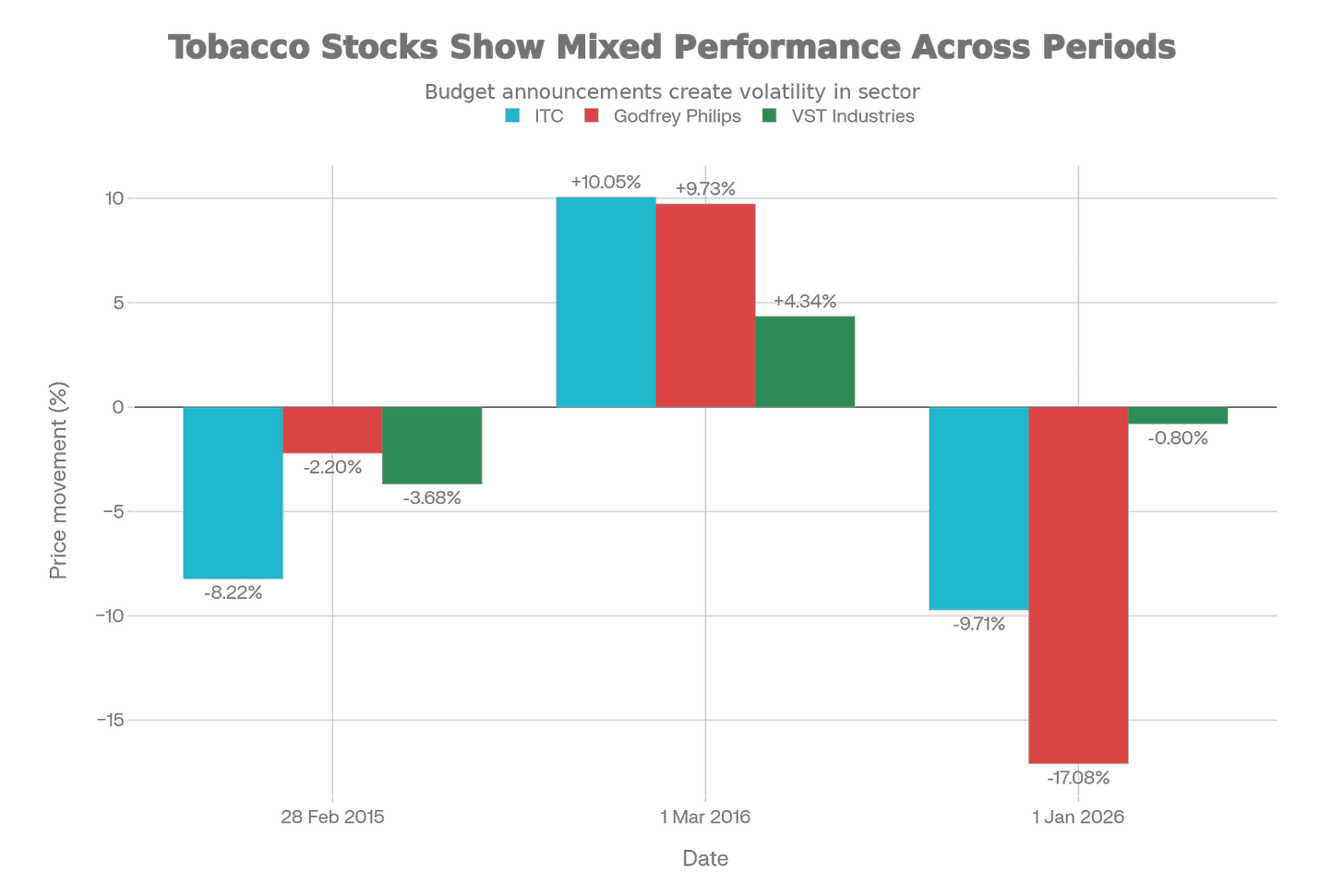

The recent fall in Indian tobacco stocks fits this pattern. It was not just about one company or a single budget change. It reflected the long, uneven way India has chosen to tax tobacco, and how those choices shape a sector that still produces steady cash flows while living with constant regulatory risk. Similar tax announcements have surfaced before, and each time the immediate market response has been loud while the underlying adjustment has been slower and more uneven.

Tobacco businesses may look simple on paper. Demand is relatively stable, products are habit forming, and brands are strong. But in reality, outcomes are shaped as much by policy as by consumers. Tax structures, duties, and enforcement often matter more than distribution or product mix. When these rules change gradually, companies adjust. When they change suddenly, even stable businesses can briefly look fragile. Seen through the lens of past tax cycles in India and compared with how other countries have approached the same problem, these episodes feel less like surprises and more like recurring features of a policy driven sector.

The Long Arc of Tobacco Taxes and the State’s Incentives

Tobacco taxes sit at the meeting point of several government priorities. From a public health view, smoking causes disease and early deaths, creating long-term costs for families and the healthcare system. From a fiscal view, tobacco provides a steady source of revenue at a time when government spending needs are rising. There is also a political and employment angle, as millions of people are linked to tobacco farming, manufacturing, distribution, and retail.

Sin taxes work for policymakers because they serve all these goals at once. They can be presented as the right thing to do for health, while also being a practical way to raise money. Increasing these taxes is often easier than raising broad-based taxes, and global health bodies continue to push countries toward higher tobacco tax levels. Over long periods, this creates a clear tendency for tobacco taxes to move higher, even if there are pauses or short-term reversals along the way.

When viewed over a decade rather than a single year, India’s tobacco tax story follows this pattern. The early 2010s saw sharp excise increases, followed by a major structural change with GST and the compensation cess. This was then followed by several years of stability, during which rising incomes made cigarettes more affordable again. The recent reset, with a new sin-tax structure and higher per-stick duties, marks the next phase in this cycle.

At each stage, the industry adjusted. Legal cigarette volumes fell during harsh tax phases, stabilised during pauses, and sometimes recovered as affordability shifted. The long-term outcome is not the sudden end of smoking, but a gradual and managed decline within a tighter regulatory framework, where cash flows can continue but the room for error keeps shrinking.

How India actually taxes tobacco?

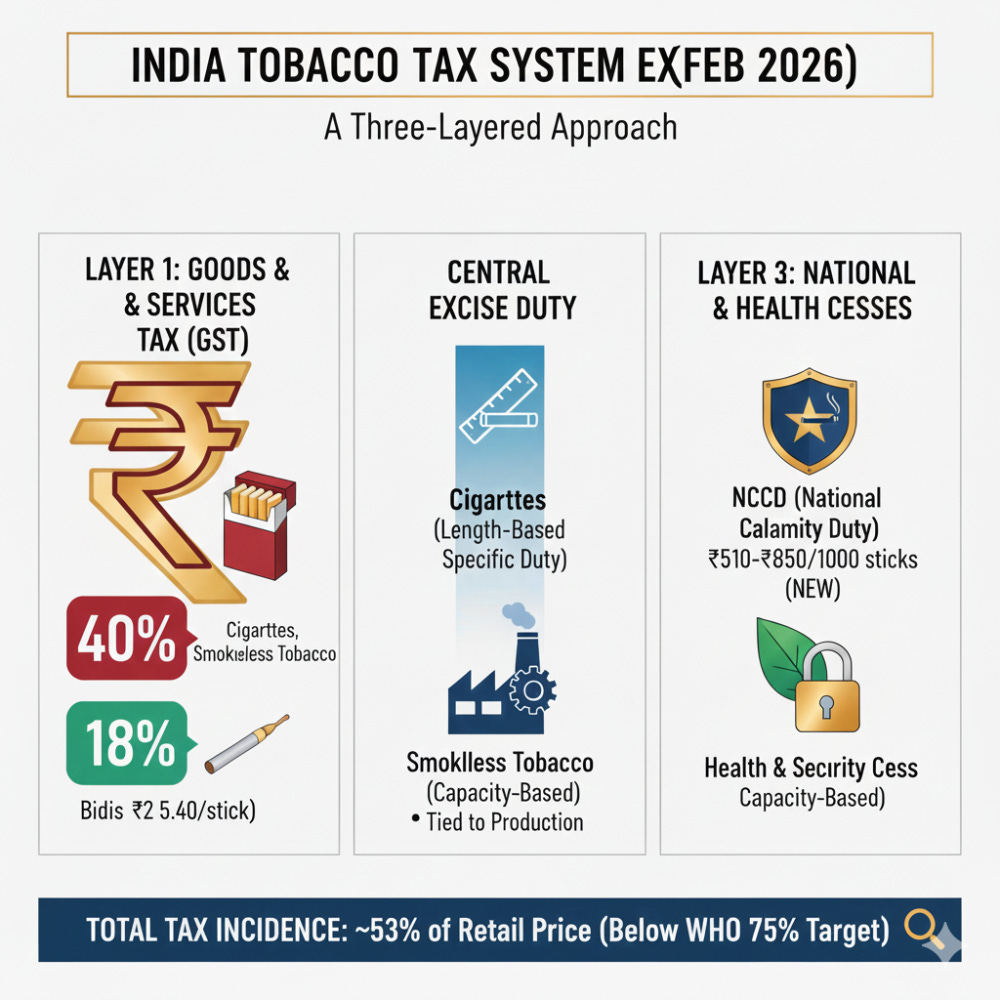

India does not tax all tobacco equally. Manufactured cigarettes sit at the top of the pyramid, bearing multiple layers of levies: Goods and Services Tax (GST), central excise duties, and special imposts like the National Calamity Contingent Duty. These levies are applied mainly through specific duties, calculated per stick and by length, rather than as a simple percentage of price.

Bidis and many smokeless products live in a different world. They face materially lower tax rates and far more fragmented enforcement. The result is a two‑tiered system: heavily taxed, organized cigarettes on one side, and lightly taxed or informally taxed products on the other. When cigarette prices rise, switching to cheaper forms of tobacco remains a ready escape hatch for many users.

This structural gap explains why cigarette companies can show decent profitability even as India’s broader tobacco consumption pattern looks messy and under‑taxed in aggregate.

2013–2017: the aggressive excise phase

The period after 2013 set the direction for modern tobacco taxation in India. In 2013–14, the basic excise duty on short, unfiltered cigarettes served as the baseline. That baseline was disrupted in 2014–15, when the new government sharply raised excise duty on the lowest-priced unfiltered cigarettes by around 151%, alongside steep increases across other length categories.

The policy intent was clear. The aim was to reduce the affordability of low-priced cigarettes, particularly for price-sensitive and lower-income smokers. This tightening continued in 2015–16, when excise duty rates were increased by 15% to 25% across cigarette lengths. Cigarettes not exceeding 65 mm faced a 25% hike, while longer cigarettes saw a 15% increase. Listed companies began warning about pressure on volumes as higher prices took effect.

In 2016–17, the pace of increases slowed slightly. Excise duty on tobacco products rose by 10% to 15%, the fifth consecutive annual increase and the smallest in three years. By then, the industry had absorbed several years of cost inflation driven mainly by policy rather than competition or input costs. Equity markets reacted with recurring volatility whenever tax changes were announced, even as long-term demand trends adjusted more gradually.

2017–2025: GST, compensation cess, and the long freeze

July 2017 reshaped how tobacco was taxed, even though the government’s broader thinking stayed the same. Cigarettes were moved into the highest GST slab of 28 percent and were also charged a Compensation Cess to replace the earlier mix of state taxes. To ensure that the overall tax burden did not fall, this cess combined a percentage-based levy with a fixed, per-unit component.

After the initial adjustments, something unusual happened. The system went quiet. From 2017 through 2025, the effective tax burden on cigarettes remained broadly unchanged. There were no new GST rate hikes and no major revisions to the cess. For an industry used to frequent policy shocks, this long period of stability felt almost like a truce.

The effects followed a familiar pattern. Legal cigarette volumes, which had been under pressure during the earlier phase of aggressive tax increases, stabilised and then recovered modestly. Earnings for listed tobacco companies improved, supported by better product mix, operating efficiencies, and the absence of fresh tax disruptions. At the same time, rising incomes and inflation slowly made cigarettes more affordable again, even though headline tax rates still looked high.

Beneath this calm, however, a constraint was building. The Compensation Cess was always temporary. As its sunset approached, the government faced a clear question of how to maintain or raise revenue from sin goods without relying on a mechanism designed to expire.

The 2026 overhaul: a new regime, not just a hike

The answer arrived in late 2025. The government created a new 40% GST “sin” slab for demerit goods, including tobacco, and paired it with a redesigned excise framework that took effect from February 1, 2026.

Under this structure, cigarettes and related products now face a higher 40% GST rate, replacing the earlier 28% slab, alongside the removal of the Compensation Cess. At the same time, a fresh layer of specific excise duties per 1,000 sticks was introduced, ranging roughly from ₹2,050 to ₹8,500 depending on cigarette length. Additional health-linked levies were also applied to some non-cigarette tobacco and pan masala segments.

Longer and premium cigarettes bear the heaviest rupee burden per stick, meaning tax incidence rises most sharply where margins used to be richest. Brokerage estimates suggest an effective portfolio-level tax increase that can approach 50% in some configurations if there is no meaningful shift in product mix.

For companies and investors, this is not just another annual hike. It is a structural reset. The tax architecture itself has been rebuilt, with a higher and narrower staircase.

The Slow Adjustment of Demand and the Risk of Illicit Trade

Cigarette demand sits in a narrow space between habit and arithmetic. Immediately after a tax increase, consumption often appears stubborn. Many smokers treat cigarettes as a necessity and cut other spending first. This creates short-term stability in volumes and can give the impression that demand is immune to higher prices. In reality, this reflects habit and inertia, not true price resistance.

Over time, higher prices begin to shape behaviour. Smokers adjust gradually by reducing consumption, shifting to cheaper brands or shorter formats, or moving to lower-tax alternatives such as bidis. Addiction slows these changes but does not prevent them. When tax hikes are concentrated on premium cigarettes, companies often see mix deterioration, where volumes hold up but profitability weakens more quickly.

These adjustments are uneven. Higher-income smokers tend to respond slowly, while lower-income users adjust faster. As legal prices rise sharply, the gap between legal and illegal cigarettes widens. Once that gap becomes large enough, smuggled and counterfeit products become more attractive, especially if enforcement does not keep pace.

The result is uncomfortable. Legal volumes shrink, organised manufacturers lose share, and the tax base itself begins to erode. Higher taxes raise revenue per cigarette, but on a smaller base, outcomes become uncertain. Enforcement matters as much as tax policy in determining whether objectives are met.

Listed Companies: The Same Shock, Different Outcomes

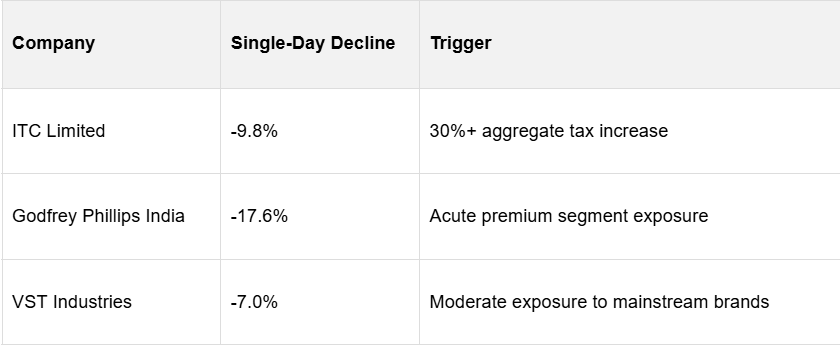

The tax overhaul affected all listed cigarette manufacturers, but not evenly. While every company faced the same policy shift, the impact depended heavily on business structure and exposure.

Companies with a higher share of premium and longer cigarettes faced sharper immediate pressure. Firms with diversified operations in FMCG, hotels, or paperboard had more flexibility to absorb stress in the cigarette segment. More specialised players may show short-term resilience but remain exposed to longer-term formalisation pressures.

Stock prices adjusted quickly as markets reassessed earnings visibility and regulatory risk. Valuation multiples compressed alongside downward revisions to profit expectations. Beneath these reactions lies a deeper question: which business models can sustain a shrinking, heavily taxed cigarette business while building durable growth engines elsewhere?

India’s place in the global tobacco tax map

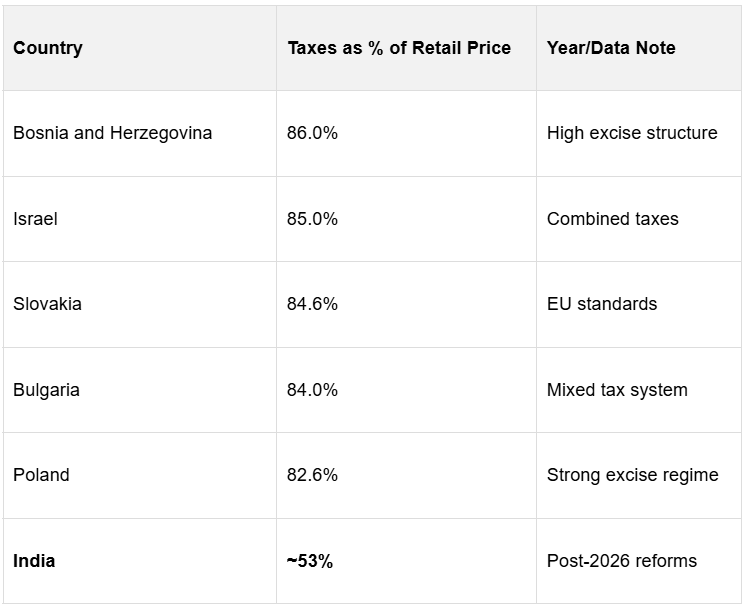

A global comparison shows how wide the gap still is. Countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Israel, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Poland tax cigarettes very heavily, with taxes accounting for more than 80 percent of the retail price. These systems rely on strong excise structures and tight enforcement, leaving little room for cheap cigarettes to exist legally.

India, even after the latest reforms, remains well below this range. Taxes are estimated to make up roughly 53 percent of the retail price of cigarettes, placing India closer to the middle of the global spectrum rather than among the most heavily taxed markets. This gap helps explain why international health bodies continue to view India as a country with scope for higher tobacco taxation.

The World Health Organization has consistently argued that taxes should make up at least 70 to 75 percent of the retail price of tobacco products. The reasoning is straightforward: higher prices discourage new users from starting and encourage existing smokers to reduce or quit over time. The WHO also prefers tax systems that rely more on fixed excise duties or strong minimum prices, which limit the availability of very cheap cigarettes and reduce down-trading.

At the same time, the comparison highlights India’s challenge. Many countries with very high tax shares have stronger enforcement, smaller informal markets, and higher average incomes. Without parallel improvements in enforcement, simply raising tax rates risks widening the gap between legal and illegal products. The table therefore shows not just where India stands today, but the careful balance future tax policy will need to strike.

The Tax Shock Ladder and the Value of Context

Tobacco tax changes are easier to understand when seen as steps on a ladder, not as one-off surprises. Small, routine hikes sit on the lower steps and are often managed without much disruption. Higher steps involve bigger shifts, such as changes in tax structure or sharp increases that directly affect prices, volumes, and profits.

The February 2026 changes sit on one of these higher steps. They did not just raise rates, but also reshaped how tobacco is taxed. Once the system moves to a higher step, the chance of further increases remains. Policy risk does not disappear after one hike. Instead, it stays in the background, making future adjustments easier to justify.

For investors, this matters when thinking about valuations. In regulated sectors, valuations fall not only because earnings are cut, but also because future cash flows feel less certain. Even if demand adjusts slowly, markets begin to factor in the possibility of more policy changes over time.

Tax headlines will keep coming, and markets will keep reacting. The aim is not to predict the next hike, but to understand where the sector now stands. In tobacco, demand alone never tells the full story. Policy direction and enforcement matter just as much. Seeing tax changes as part of a cycle helps explain why investors remain cautious on valuations, even when the business itself looks stable.

Lingo of the Week: Policy Rhythm

Policy rhythm refers to the recurring pattern in which governments tighten, pause, and then reset regulations over time, especially in heavily regulated sectors. These shifts rarely move in straight lines. Instead, they arrive in waves, often separated by long periods of calm.

For example, India’s tobacco sector saw sharp tax hikes in the early 2010s, a long pause after GST, and then a major reset in 2026. Markets reacted loudly at each step, but companies adjusted gradually. Investors who understood this rhythm focused less on headlines and more on where the sector stood in the policy cycle.

Pocketful isn’t just another trading platform - we’re your partners on the journey to financial freedom.

Thank you for reading!

👀 Stay tuned. Stay diversified.

Until next time,

Team Pocketful.

Follow Us: Website

Download Our App: Available on Google Play & Apple App Store

Solid breakdown of how tax policy creates recurring cycles in sin-tax sectors. The distinction between short-term market reactions and long-term structural adjustments is spot-on, especially when policy changes arrive in waves rather than smooth increments. I've seen similiar patterns play out in alcohol markets where companies absorb the first shock, then slowly restructure thier portfolios downward. The gap between legal and illicit products is probably the most underestimated variable here.